Hogan was one of the greatest golfers of the 20th century, an accomplishment he achieved through tireless repetition. He simply loved to practice. Hogan said, “I couldn’t wait to get up in the morning so I could hit balls. I’d be at the practice tee at the crack of dawn, hit balls for a few hours, then take a break and get right back to it.” 1

For Hogan, every practice session had a purpose. He reportedly spent years breaking down each phase of the golf swing and testing new methods for each segment. The result was near perfection. He developed one of the most finely-tuned golf swings in the history of the game.

His precision made him more like a surgeon than a golfer. During the 1953 Masters, for example, Hogan hit the flagstick on back-to-back holes. A few days later, he broke the tournament scoring record. 2

Hogan methodically broke the game of golf down into chunks and figured out how he could master each section. For example, he was one of the first golfers to assign specific yardages to each golf club. Then, he studied each course carefully and used trees and sand bunkers as reference points to inform him about the distance of each shot. 3

Hogan finished his career with nine major championships—ranking fourth all-time. During his prime, other golfers simply attributed his remarkable success to “Hogan’s secret.” Today, experts have a new term for his rigorous style of improvement: deliberate practice.

Deliberate practice refers to a special type of practice that is purposeful and systematic. While regular practice might include mindless repetitions, deliberate practice requires focused attention and is conducted with the specific goal of improving performance. When Ben Hogan carefully reconstructed each step of his golf swing, he was engaging in deliberate practice. He wasn’t just taking cuts. He was finely tuning his technique.

While regular practice might include mindless repetitions, deliberate practice requires focused attention and is conducted with the specific goal of improving performance.

The greatest challenge of deliberate practice is to remain focused. In the beginning, showing up and putting in your reps is the most important thing. But after a while we begin to carelessly overlook small errors and miss daily opportunities for improvement.

This is because the natural tendency of the human brain is to transform repeated behaviors into automatic habits. For example, when you first learned to tie your shoes you had to think carefully about each step of the process. Today, after many repetitions, your brain can perform this sequence automatically. The more we repeat a task the more mindless it becomes.

Mindless activity is the enemy of deliberate practice. The danger of practicing the same thing again and again is that progress becomes assumed. Too often, we assume we are getting better simply because we are gaining experience. In reality, we are merely reinforcing our current habits—not improving them.

Claiming that improvement requires attention and effort sounds logical enough. But what does deliberate practice actually look like in the real world? Let’s talk about that now.

One of my favorite examples of deliberate practice is discussed in Talent is Overrated by Geoff Colvin. In the book, Colvin describes how Benjamin Franklin used deliberate practice to improve his writing skills.

When he was a teenager, Benjamin Franklin was criticized by his father for his poor writing abilities. Unlike most teenagers, young Ben took his father’s advice seriously and vowed to improve his writing skills.

He began by finding a publication written by some of the best authors of his day. Then, Franklin went through each article line by line and wrote down the meaning of every sentence. Next, he rewrote each article in his own words and then compared his version to the original. Each time, “I discovered some of my faults, and corrected them.” Eventually, Franklin realized his vocabulary held him back from better writing, and so he focused intensely on that area.

Deliberate practice always follows the same pattern: break the overall process down into parts, identify your weaknesses, test new strategies for each section, and then integrate your learning into the overall process.

Here are some more examples.

Cooking: Jiro Ono, the subject of the documentary Jiro Dreams of Sushi, is a chef and owner of an award-winning sushi restaurant in Tokyo. Jiro has dedicated his life to perfecting the art of making sushi and he expects the same of his apprentices. Each apprentice must master one tiny part of the sushi-making process at a time—how to wring a towel, how to use a knife, how to cut the fish, and so on. One apprentice trained under Jiro for ten years before being allowed to cook the eggs. Each step of the process is taught with the utmost care.

Martial arts: Josh Waitzkin, author of The Art of Learning, is a martial artist who holds several US national medals and a 2004 world championship. In the finals of one competition, he noticed a weakness: When an opponent illegally head-butted him in the nose, Waitzkin flew into a rage. His emotion caused him to lose control and forget his strategy. Afterward, he specifically sought out training partners who would fight dirty so he could practice remaining calm and principled in the face of chaos. “They were giving me a valuable opportunity to expand my threshold for turbulence,” Waitzkin wrote. “Dirty players were my best teachers.”

Chess: Magnus Carlsen is a chess grandmaster and one of the highest-rated players in history. One distinguishing feature of great chess players is their ability to recognize “chunks,” which are specific arrangements of pieces on the board. Some experts estimate that grandmasters can identify around 300,000 different chunks. Interestingly, Carlsen learned the game by playing computer chess, which allowed him to play multiple games at once. Not only did this strategy allow him to learn chunks much faster than someone playing in-person games, but also gave him a chance to make more mistakes and correct his weaknesses at an accelerated pace.

Music: Many great musicians recommend repeating the most challenging sections of a song until you master them. Virtuoso violinist Nathan Milstein says, “Practice as much as you feel you can accomplish with concentration. Once when I became concerned because others around me practiced all day long, I asked [my professor] how many hours I should practice, and he said, ‘It really doesn’t matter how long. If you practice with your fingers, no amount is enough. If you practice with your head, two hours is plenty.’” 4

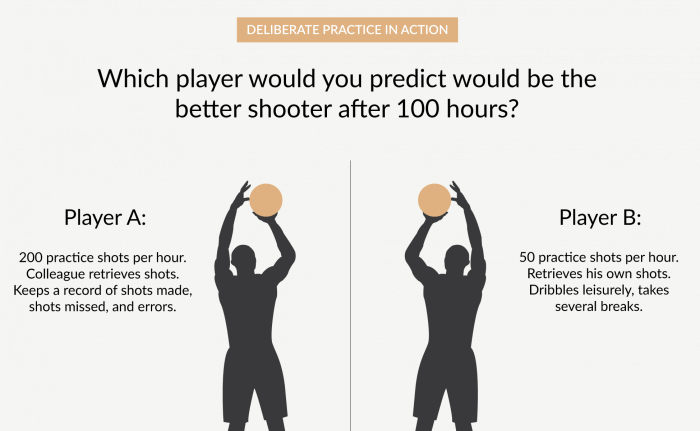

Basketball: Consider the following example from Aubrey Daniels, “Player A shoots 200 practice shots, Player B shoots 50. The Player B retrieves his own shots, dribbles leisurely and takes several breaks to talk to friends. Player A has a colleague who retrieves the ball after each attempt. The colleague keeps a record of shots made. If the shot is missed the colleague records whether the miss was short, long, left or right and the shooter reviews the results after every 10 minutes of practice. To characterize their hour of practice as equal would hardly be accurate. Assuming this is typical of their practice routine and they are equally skilled at the start, which would you predict would be the better shooter after only 100 hours of practice?”

Perhaps the greatest difference between deliberate practice and simple repetition is this: feedback. Anyone who has mastered the art of deliberate practice—whether they are an athlete like Ben Hogan or a writer like Ben Franklin—has developed methods for receiving continual feedback on their performance.

There are many ways to receive feedback. Let’s discuss two.

The first effective feedback system is measurement. The things we measure are the things we improve. This holds true for the number of pages we read, the number of pushups we do, the number of sales calls we make, and any other task that is important to us. It is only through measurement that we have any proof of whether we are getting better or worse.

The second effective feedback system is coaching. One consistent finding across disciplines is that coaches are often essential for sustaining deliberate practice. In many cases, it is nearly impossible to both perform a task and measure your progress at the same time. Good coaches can track your progress, find small ways to improve, and hold you accountable to delivering your best effort each day.

Humans have a remarkable capacity to improve their performance in nearly any area of life if they train in the correct way. This is easier said than done.

Deliberate practice is not a comfortable activity. It requires sustained effort and concentration. The people who master the art of deliberate practice are committed to being lifelong learners—always exploring and experimenting and refining.

Deliberate practice is not a magic pill, but if you can manage to maintain your focus and commitment, then the promise of deliberate practice is quite alluring: to get the most out of what you’ve got.

Thanks for reading. You can get more actionable ideas in my popular email newsletter. Each week, I share 3 short ideas from me, 2 quotes from others, and 1 question to think about. Over 3,000,000 people subscribe. Enter your email now and join us.